The Survivors’ Temple

On Manhattan’s Upper West Side in the 1960s, my parents didn’t belong to a synagogue, but they found an ad hoc congregation in an unlikely place for the High Holidays

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

Tablet Magazine

Although I grew up in a traditional Jewish home on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, for much of my childhood in the 1960s, my survivor parents didn’t belong to a synagogue. In our neighborhood, the larger congregations were led by uberwealthy and unaccented Jews whom my parents found snobby and intimidating. They weren’t the only ones. While American Jews donated generously toward the survivors’ material needs, they rarely offered their friendship.

“Even the most well-meaning American Jews found it difficult to relate to survivors,” explains journalist Seth Stern in Speaking Yiddish to Chickens: Holocaust Survivors on South Jersey Poultry Farms. “They had no conception of what survivors had endured or how to talk about it.”

Day after day, my father prayed alone at the kitchen window. As the High Holidays beckoned, however, he and my mother felt pulled to the formal worship they remembered from the Old Country.

But where could they go?

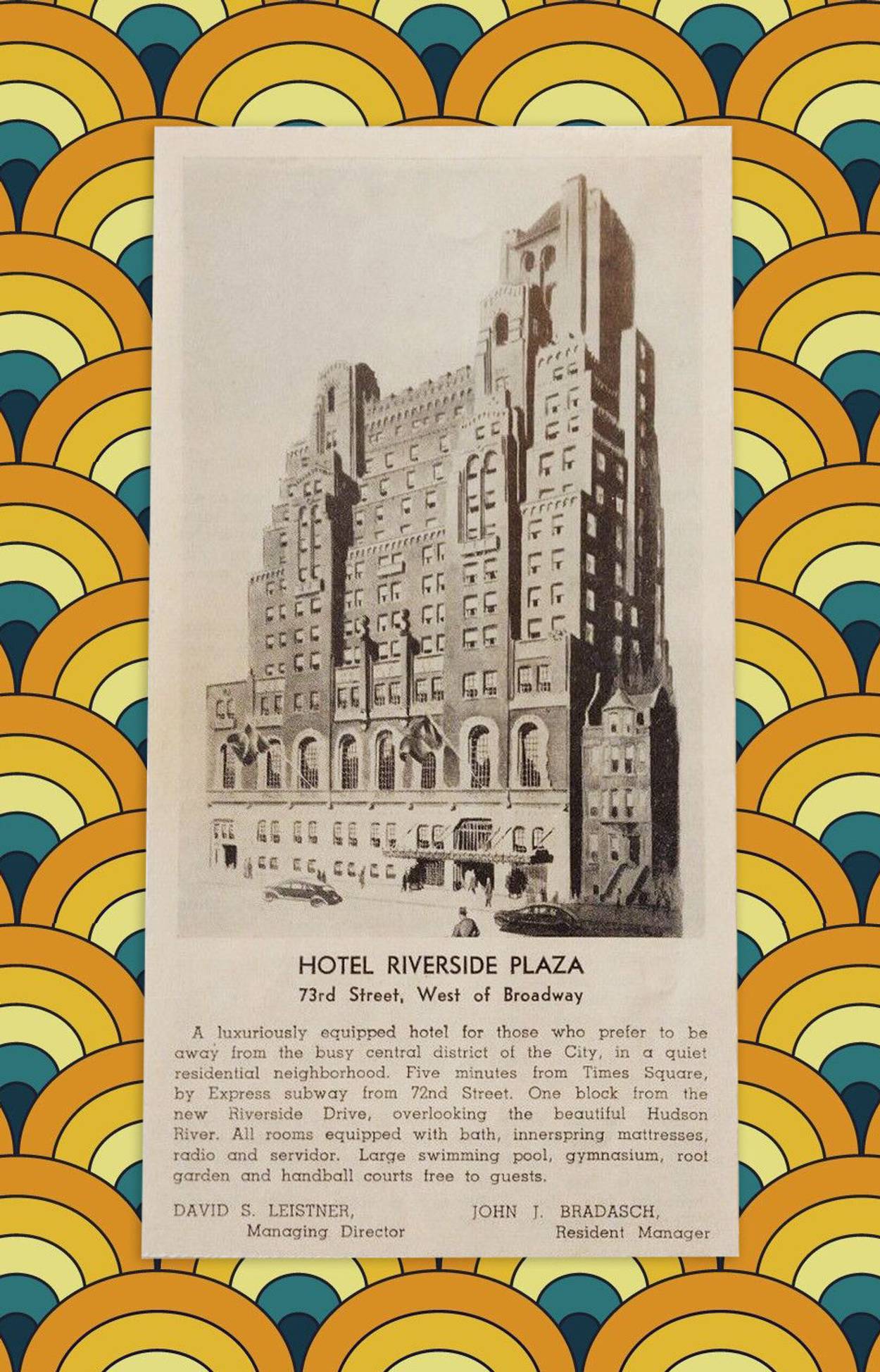

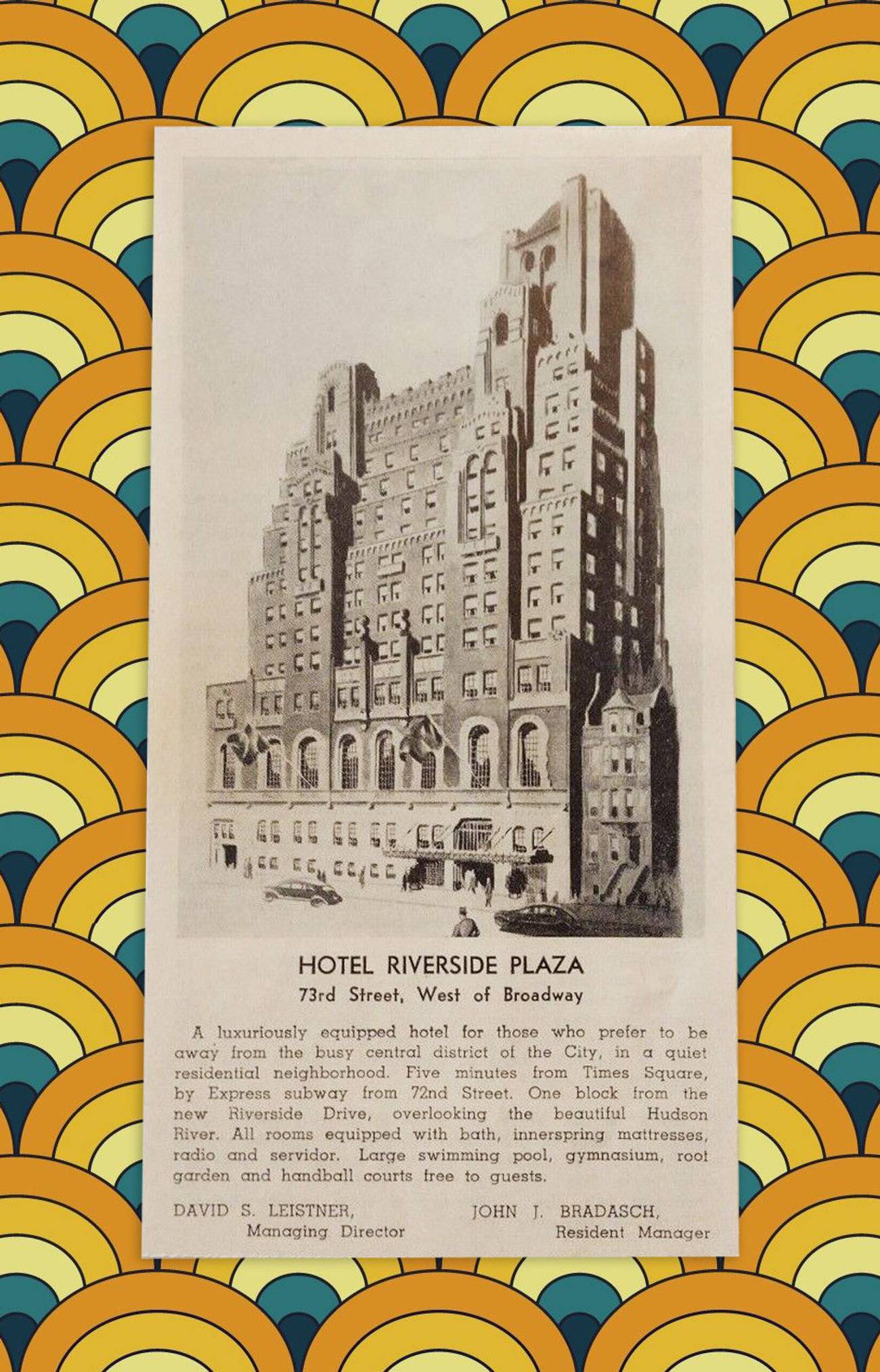

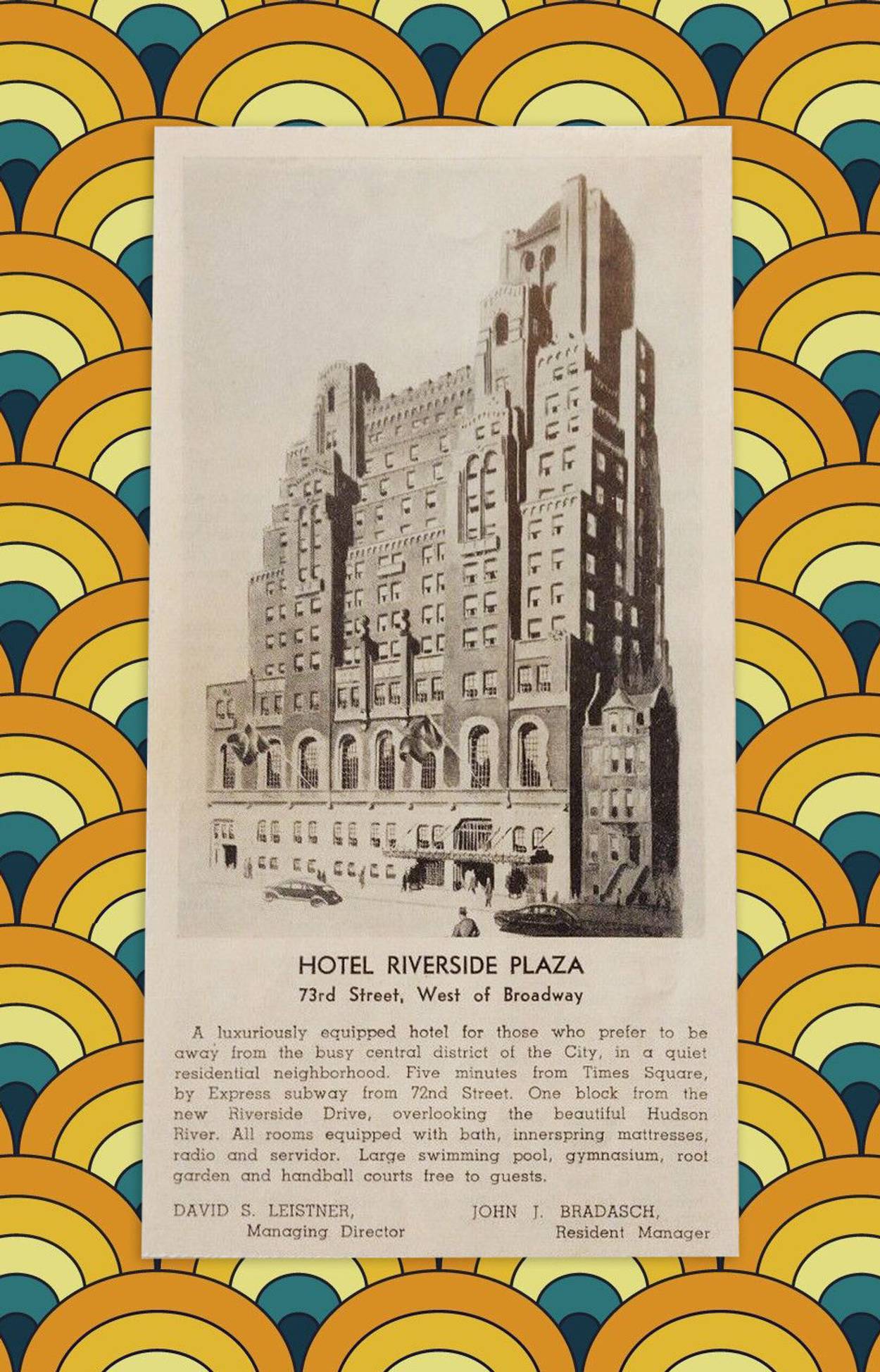

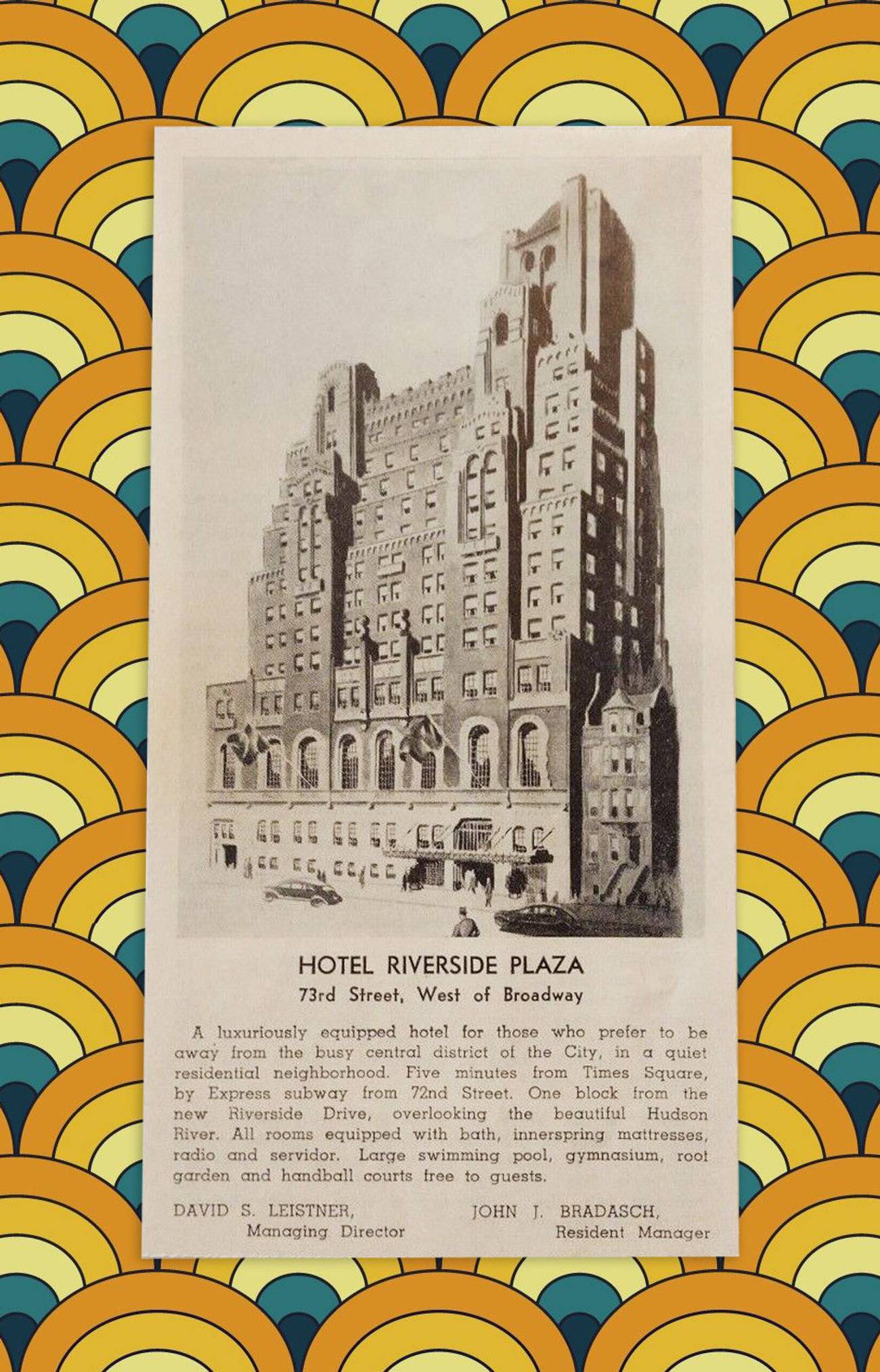

As neither hailed from Hasidic homes, the neighborhood shtieblach—one-room synagogues where they might have found landsmen—held no appeal. Instead, they affiliated with a High Holidays-only prayer community that met at the Riverside Plaza Hotel. This ad hoc shul was no small thing: The hotel auditorium could seat 1,400 comfortably and up to 3,000 in a pinch. From what I remember, the place was full.

Who came? Mostly, other survivors.

The hotel had seen better days. Erected in 1927 as a posh clubhouse for Freemasons, by the early 1960s when my family worshipped there, the elegant 18-story Romanesque-style tower had morphed into a single-room-occupancy hotel. Despite the shabby setting, the worshippers—who less than two decades earlier had been human skeletons—were dressed to the nines, or as they’d say it, fahrputzed. Both genders wore hats: for men, fedoras with feathers tucked in the brim, and for the ladies, a colorful variety of shapes and sizes. The men, most of whom worked as diamond cutters, jewelers, or garment workers, came in suits and neckties, their wives in fancy dresses, high heels, and, as was the style in those days, gloves. At the center of this display were their American-born offspring dressed in the style of the Kennedy children.

The service was grand and operatic, a mode of worship favored by European Jews. By the following decade, this style would be replaced by Shlomo Carlebach and Debbie Friedman. The high-ceiling auditorium provided an acoustically friendly venue setting for these latter-day Levites, the cantor in his white robes and puffy white yarmulke backed up by a male choir.

My parents loved it, especially my father. For weeks afterward, our home resounded with the sound of him singing the cantor’s melodies in his own sweet tenor.

I don’t think our ad hoc congregation had a rabbi or a sermon. Outside of the liturgy, which few of the worshippers understood—most had their education truncated by the war—there were no words to rouse the crowd to repentance, atonement, or drawing closer to God.

My parents didn’t offer me any explanations. They came and they dragged my brother and me along year after year, going to the trouble of outfitting us from head to toe, purchasing tickets, shuttering their factory, and giving their employees three days of paid vacation.

Why?

It wasn’t about God, claims Yossi Klein Halevi. “They (meaning the survivors) were preserving the rituals of the kedoshim, the martyrs who had died in the Holocaust,” he explains in Memoirs of a Jewish Extremist, his memoir about growing up in a survivor family. “None of us believed,” writes Halevi, quoting his survivor father.

I’m not sure I agree. The survivors I knew believed too much—they were angry that God hadn’t graced them with an Exodus-style miracle. Yet, none would have considered staying home or going to work on the High Holidays.

At the Riverside Plaza shul, the main event wasn’t shofar blowing, Kol Nidre, or Neilah, but Yizkor, the Yom Kippur memorial service, when dozens more worshippers, some without tickets, filled the room.

While the ticketholders brought spouses and children, these worshippers came alone, some muttering to themselves and displaying signs of mental illness, which in those days often went untreated. Here, they were welcomed. Here, their tears could flow freely, tears they hadn’t been able to shed when their loved ones were gassed in the camps or gunned down in forests.

“They never had a chance to bury their loved ones or sit shiva,” writes Stern. “They didn’t know the exact day of death on which to say Kaddish, they couldn’t visit the gravesite, so they went to Yizkor.”

It’s unlikely they realized this, but the Riverside Plaza survivor congregation had picked a particularly apt spot for their services. The structure had been designed as a replica of Solomon’s Temple, the holiest spot in the historical Jewish world. The building is “the only true-to-size rendering of King Solomon’s Temple that exists in the world today,” wrote Bruno Bertuccioli in his book The Level Club: A New York City Story of the Twenties: Splendor, Decadence and Resurgence of a Monument to Human Ambition.

Embedded into its brickwork are hexagrams—the six-pointed stars the survivors would have identified as Magen Dovids—and friezes of King Solomon and his helper, the Phoenician King Hiram. In Jewish tradition, the temple is the source for healing and inner peace.

Perhaps the Riverside Plaza service, set in the world’s only Temple facsimile, absorbed more of the Temple’s spiritual energy, especially when it filled with survivors and their progeny. The healing did occur, at least partially. While my parents never overcame their wartime traumas—I don’t think that was possible for anyone—they experienced enough healing to be able to raise a family, build a successful business, and eventually reenter the Jewish community by becoming members of two synagogues. They also lived long enough to cradle grandchildren and, in my mother’s case, great-grandchildren. Many other survivors could share similar stories.

The Riverside Plaza, too, experienced a revival. After decades in disgrace, including a period during the 1970s when it housed a particularly disreputable drug rehabilitation center, the building now known as the Level Club has been transformed into swanky condominiums. Sadly, it no longer boasts a synagogue, not even an ad hoc one—the need for one no longer exists. Still, that long ago service has stayed in my heart and the prayers said there by the most broken members of the Jewish nations will last into eternity.

Carol Ungar’s writing has appeared in Next Avenue, Forbes, NPR, the Jerusalem Post Magazine, and Fox News. She also leads memoir writing workshops on Zoom.